1:00 PM – 2:00 PM (PDT) | Aniplex Live Stream | Sunday 5 July 2020

Panel Description: Anime producers will talk about behind the scenes of anime production. Master of Ceremonies/Host: Hisanori Yoshida Guests: Shizuka Kurosaki (Aniplex, Producer) Masami Niwa (Aniplex, Producer), Atsushi Kaneko (A-1 Pictures, Producer), Toshikazu Tsuji (CloverWorks, Producer)

_

Credit: Krow Smith | @coffeewithkrow & Peggy Wood | @pswediting

How Do You Produce An Anime?

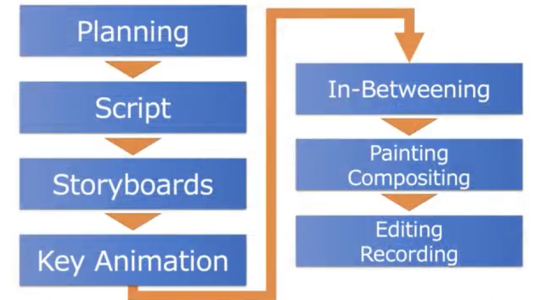

Here’s the process for an anime: first proposal, the script, the storyboard, the key animation, painting, compositing, editing, and recording and that’s when it’s ready to be shown.

Step 1: Planning

There are mainly three different ways that proposals tend to come in during this planning stage. The first is when the publisher tells us about one of their hit products (games, a manga, etc.) and they ask us about adapting it into an anime. The second is when we find a series we like from a light novel or manga we’re reading already. Like, “Hey, this is cool!” Then we ask the publisher/get their permission to make the anime. The third is when a producer from an anime studio, or a director, or a staff member brings us something that they personally want to do. These are the most likely ways we come to a proposal for a new series and, of them, the third probably happens the most often.

Next comes the decision stage. A few more patterns emerge when we’re discussing whether to adapt or create an original series.

With originals, you are starting from scratch so the project is much more involved and time-consuming. Generally, a lot of staff members are involved and all of them want different things and, on top of that, the producer’s job is to make sure it does well. That it sells well, that it’s received well, that the team feels good or great about the project, and so on. So we have to find a way to respect everyone’s vision, while also guiding the project to profitability, which is pretty demanding. This also includes what I want to do as a producer. It’s fun to create something from scratch, but it also comes with so much risk. For example, originals don’t have a built-in fanbase, they don’t have the same support.

Shizuka Kurosaki provides an anecdotal example of a series he started 8 years ago that he is still working on from time to time. According to him, the series is still nowhere close to being produced. It’s just a sign of how hard it is to get it all to come together, especially when things change as time goes on.

Adaptations are different but still tough and demanding. First, you have great source material. Naturally, there are fans of the source material with what they want for the original. When we depict it through anime, there are things that were fine in the source but have to be changed for animation. We are pretty sensitive about how the original’s fans would see the results of our decision-making. Needless to say, that is a struggle that we don’t face when creating an original anime.

One of the hardest parts about adaptations is that novels and manga, which are largely still images and text, as opposed to anime, which is video, all have different rules of depiction. And when the time comes for us to make changes, we’re presented with options.

Depending on what the scene is, certainly, some viewers will say, “Why couldn’t you just stay faithful to the original?” However, there are also times when changing it to be more anime-like gives it a shot of energy absent from the printed version. There’s really no right answer so the process is like groping around in the dark and hoping that you find what works.

Producers don’t tend to have a lot of free time and when they do, like Masami Niwa mentioned, it’s mostly spent on things that will help at work. For example, reading what’s trending in novels or manga, watching movies, and even other animes from other companies. While it may seem like entertainment and is often enjoyable, these all serve one’s work as a producer in the field.

Step 2: Scripting

Generally, a “scenario meeting” or script meeting is held first. It’s when we look at what a writer has come up with and plan out some “book reading time.” For adaptations, it means reading the source text(s). Additionally, the planning producers and animation producers hold these meetings where the discussions start with talking about the potential series and gathering the team/assembling our staff. We already have a director in place by the time we have the first script meeting. The script is only done once the staff, including the director, gathers and is written.

Live-action scripts have hardly any screen direction when compared to anime scripts. Anime scripts are packed full of exposition. In the case of live-action scripts, if it’s like an ordinary office story. You pretty much recreate normal life. Whereas in an anime script, even if it’s an ordinary office story, there might be an employee with mind-blowing supernatural abilities. To depict something that doesn’t exist in real life, you need screen direction. And in the eyes of someone from another industry, I think it would seem like a really complex script because of the sheer amount of detail regarding action, layout, and such.

Step 3: Storyboarding

The storyboard is drawn from the script. Normally, the director draws the storyboards. But since the number of episodes keeps increasing for TV series, lately we’re seeing several storyboard artists dividing the labor.

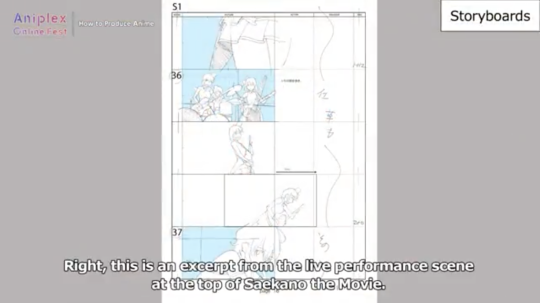

Here are some samples of storyboards from Saekano the Movie: Finale, one of Toshikazu Tsuji’s past projects shared with the panel:

Envelopes like these, sometimes referred to as “shot envelopes” contain the layout drawings and artwork that become the key animations and in-betweens of individual scenes. By the end, all the materials that make up each scene and the finished ones are all inside one of these envelopes.

This is what storyboards look like:

This is an excerpt from the live performance scene at the top of Saekano the Movie.

Using Saekano the Movie as an example–it was a tad difficult to associate the “live scene” of the script to the animation. In the script, the directors and team have endless discussions of what they want to see within however many seconds of the animation. This is described to the animators, the people who are actually drawing the actions/storyboards/etc., who only remember parts of the conversation or only get a few words and they have to create these complex drawings after hearing the phrase “live scene.” Sometimes there is a lot of direction in those discussions while in the original novel it may just say, “they fought, they won,” but the battle leads into an epic space war.

Producers are always excited to see the storyboards. They know it must be a lot of work, hard work, to get them but they’re amazing. Animators sometimes get mad at the scripts and the different “grammar” of the adaptations between the novel and the anime script, but they do great work. To the producers, it’s almost the same feeling as a fan seeing the anime for the first time.

Back to the Saekano the Movie example, in the live performance scene above, the animator that was asked to draw the scene knew how to use the instruments being played. That experience is indispensable in some cases as it helps make the movements more accurate and realistic. In the worst case scenario, producers sometimes go with motion capture or use recordings of live performances that are then 3-D rendered for the key animations.

Step 4: Key Animations

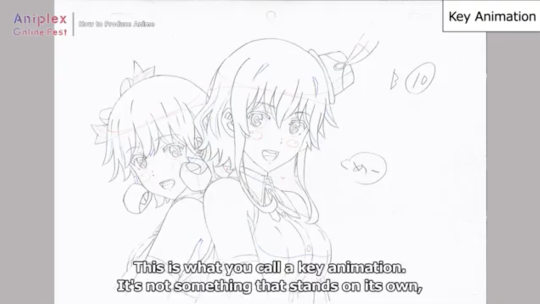

Key animations are a part of the storyboard. They are often more detailed images used to depict specifics in individual scenes, with other frames used for movements happening in between. They are often discussed and detailed during and post conversations between the animator, director, super director, and the producer.

The above is an example of a key animation. It’s not something that stands on its own, rather, they’re made out of multiple drawings. This is where she utters the “meee” from the lyrics (Saekano the Movie). This key animation is to clarify that she’s saying “meee” from the lyrics as the shape of her mouth changes. The words on the page are helpful, but not necessary.

Next we see a sample of timesheets (image below).

Time sheets are like a blueprint. This is a 3-second shot described in a timesheet and it contains all of the information going into that 3 seconds.

At the top of the timesheets are numbers and that’s where they write where they want the key animation positions to be. Since this is a live performance scene, it ends on a unique shot, and for normal shots, they’d insert some dialogue, or time a movement there. There are also instructions for Compositing. The timesheet is filled with all these details.

There are all kinds of key animations, and a key animation that’s cleared every step in the process is what we call an in-between.

Step 5: In-Betweening

In-betweening is creating the materials that fill up the spaces between the key animation positions. Since anime is all about movement from point a to point b, we have several pages to make characters and items move in-between the two points.

(Image from: https://boords.com/animatic/what-is-the-definition-of-an-animatic-storyboard)

The above is an example. On the left, you see and anamatic–which is essentially a storyboard shown in order to create the story. The frozen frames make up the key animations prior to details. On the right, you have the fully animated piece. All of the movement seen in-between those key animations seen on the left, come together to create the moving animation seen on the right is an example of the in-betweening discussed here.

Going back to the time sheet–if you look closely you can see numbers going vertically which say 1-2-3-4 etc. Those are key animations. And the tiny dots you see in between, those are in-between animations. So drawing between the first and second key animations is the job of the in-between animator for this scene.

Step 5: Painting & Compositing

Next comes painting and composition–it’s where all the colors are applied. Years ago, this used to be done with real paint. Today though, this process is usually done digitally and it’s done for every frame (all of the in-betweens, key animations, etc.). The painting process includes Compositing. It’s not until after it’s been Composited that it’s truly finished.

During compositing, all of the different piece of paper shown in this panel so far are transformed into the animation you later see. Compositing gets the timesheet you just saw, with the materials for the backgrounds and cells, the animations and such, and then they work from that blueprint to create the full animation.

In the images seen above from the Saekano the Movie example, what you’ve seen is less than a single second but it took that much work to get there. As the producer, sometimes it’s your job to step in and help if the animators taking on that workload get overwhelmed.

Animators probably leave their personal mark somewhere on the key animations they create, something that only they know about. So if that storyboard can be thought of as a blueprint for drawing, then the key animations have their character settings, and they’re drawn by diverse people with unique intentions. That’s what we try to go for, and it’s really great to be able to see it all before anyone else as a producer. Like a character who’s never made a gesture like that in such a situation in the original story, but then when a certain animator draws that character, you’ll see that gesture and it will bring life to the image. If you start looking, it’s pretty endless. But seeing all these personal stamps is what makes it so intriguing. As long as it doesn’t stray far from the story, it’s not usually a problem for the producer. It what makes anime adaptation so enjoyable for one of the panelists.

Final Step (6): Recording & Editing

After the visuals are done, comes the sound production and voice actors. Once you find the people for the roles needed, they move onto recording, and then background music is added, and finally you get the finished product that viewers see. Editing happens then too, though it also happens throughout the process as things are added and taken out over the course of production.

An example of the finished product:

The producer can change the whole feel of the show as they often make executive decisions on music, editing, marketing, etc. They have to oversee the process, as we’ve seen throughout the panelists’ discussion on the production process. It’s worth understanding from an analytic point of view as you see how their styles, focuses, and insight can influence the creation of a series.

Copyedited by: Krow Smith | @coffeewithkrow

Discover more from The Anime View

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Aniplex Online Fest – How to Produce an Anime – Notes!”